Okinawa’s unique culture and languages are slowly disappearing. When we say “Okinawa,” it is important to keep in mind that Okinawa is one island in the diverse Ryukuan archipelago. The Ryukus is home to several islands and languages. After a century of Japanese rule Okinawa’s unique culture and language and that of its sister islands are in danger of being wiped out.

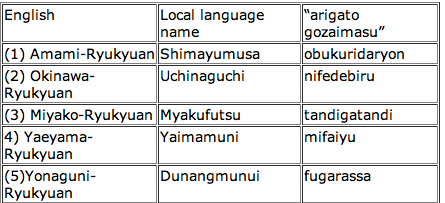

Below is a chart of the different Okinawan languages, their local names, and how they would say: “Thank You.” When we compare the local Okinawan expressions against mainland Japan’s “arigato gozaimasu,” we soon realize that we are talking about different languages, not dialects.

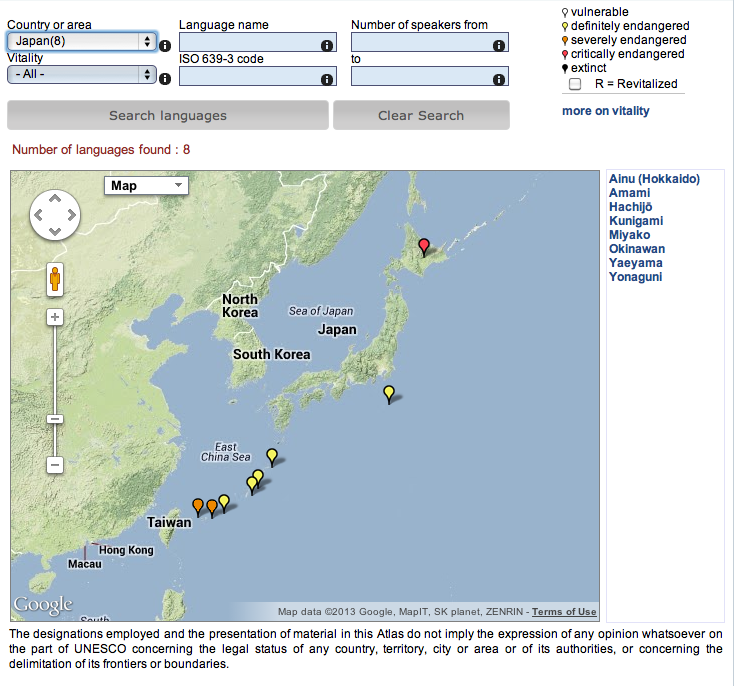

Below is a map showing the endangered languages in Japan.

The yellow tabs indicate “definitely endangered,” while the orange tabs indicate “severely endangered.”

Languages do not die overnight, but slowly and gradually. They are gradually pushed out of the schools and government offices, and confined to the privacy of the homes. After several generations knowledge of the culture and language begin to fade away, then disappear forever. A chart showing the stages of language degeneration can be found on Endangered-Languages.com.

The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus published an article “Wanne Uchinanchu: I Am Okinawan” by Fija Bairon and Patrick Heinrich in 2007. The article is about the slow death of the Okinawan language and the attempts by some to revive the Okinawan language and culture. Fija and Heinrich noted:

The Ryukyuan languages are severely endangered today, because domains of Ryukyuan language uses have been continuously lost since the start of Japanese language spread in the 1880s. The expansion of one language always coincides with the contraction of another. Languages are thus not lost word by word but domain by domain. Once those domains in which the language is naturally transmitted are lost, the language is endangered in its survival. From that point on, languages are lost speaker by speaker. While Japanese was largely restricted to official domains until the 1940s, shift to Japanese in private domains such as the family and the neighbourhood meant that natural intergenerational language transmission was interrupted. Since the 1940s two predominantly Japanese monolingual generations have been raised in the Ryukyu Islands (Heinrich 2004). It now only takes knowledge about average life expectancy, Ryukyuan demographics and a little mathematics to calculate the future decline of the Ryukyuan languages in the event that no effective counter action is taken. I will refrain from doing such maths here since language shift can be reversed. – See more at: http://www.japanfocus.org/-Fija-Bairon/2586#sthash.wK5DuAX6.dpuf

The Okinawan language is dying in part because of Japan’s nationalistic policies. In its quest to become a modern nation-state the Japanese government sought to eliminate regional differences and impose national uniformity. Japan’s national bureaucracy sought and still seeks to impose linguistic uniformity throughout its territories. One vivid example of the attempts to impose linguistic standardization is the “hogen fuda” or “dialect tag.” It was the practice to shame students who spoke non-Japanese by hanging the “hogen fuda” around their neck. This was meant to be a badge of shame. Its purpose was to discourage students from speaking their native language and force them to adopt the new official language. Nowadays less visible means are used. The approval process for school textbooks by Japan’s Ministry of Education not only ensures the dissemination of the Japanese language, but also an “impartial” presentation of Japan’s history.

Philippa Fogarty of BBC News described the dramatic language shift in post-World War II Okinawa. Even as late as 1945 many Okinawans still spoke Uchinaaguchi. Then during the 1950s and 1960s in reaction to the US military presence there was a push to become more Japanese. Parents stopped using Uchinaaguchi with their children thinking that by learning Japanese their children would have a better chance of getting jobs. Today Uchinaaguchi is spoken only among the elderly.

After more than a century of political hegemony, assimilation, and centralization, there is a need for an alternative discussion that focuses on the themes of autonomy, decentralization, cultural diversity, and indigeneity. Hawaii’s recent history contains valuable lessons that can stimulate discussion of alternative paths to the future.

Cultural Revival In Hawaii

Hawaiian was the dominant language until 1893 when the sugar planters with the aid of the US military overthrew the Hawaiian kingdom. Then in 1898 Hawaii became a US possession and English became the new official language. Hawaii’s political and social history in the twentieth century is the story of how Americans sought to assimilate Hawaii’s multi-cultural society into mainland haole culture. This involved the marginalization of Hawaiian, the language of the indigenous inhabitants, and the suppression of Pidgin, a creole that originated on Hawaii’s plantations and is spoken by about half of Hawaii’s residents today. See: “Language and Power in Hawaii.”

In recent years there has been a cultural revival in Hawaii. After decades of pressure to assimilate into mainland American culture, the tide has shifted and many people in Hawaii are looking into their family history and seeking to recover their cultural heritage. In the 1980s there was a growing interest among the Hawaiians in reviving the Hawaiian language. A similar interest began among the Locals to affirm Pidgin as an expression of Local identity.

The 1980s also saw the flourishing in Uchinanchu pride through the construction of the Hawaii Okinawan Center and the popularity of the Okinawan Festival. For more information on the Okinawan revival in Hawaii, see Wesley Ueunten’s doctoral dissertation: “The Okinawan revival in Hawai’i: Contextualizing culture and identity over diasporic time and space.”

This has led to greater interest in Uchinaaguchi (the Okinawan language). At present Uchinaaguchi is being taught at the University of Hawaii at Manoa (JPN 472) as well as in less formal settings in several locations in Hawaii. It has been said that the revival of Uchinanchu culture in Hawaii may one day bring about a similar revival in Okinawa.

Robert Arakaki